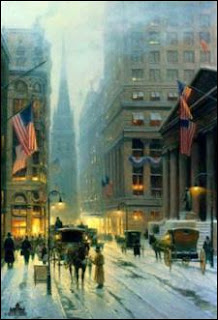

In the autumn of 1929 came the catastrophe which so few had anticipated but which in retrospect seems inevitable--prices broke on the New York Stock Exchange, dragging down with them in their fall, first the economy of the United States itself, subsequently that of Europe and the rest of the world. Financial losses of such magnitude had never before been known in the history of capitalist society, and the ensuing depression was also unprecedented in scope.

There had always been business crises; economists had come to take them as normal and even to chart a certain regularity in their occurrence. But this one dwarfed all its predecessors: no previous depression had remotely approached it in length, in depth, and in the universality of impact. Small wonder that countless people were led to speculate whether the final collapse of capitalism itself, so long predicted by the Marxists, was not at last in sight.

On October 24, "Black Thursday," nearly thirteen million dollars worth of stocks were sold in panic, and in the next three weeks the general industrial index of the New York Stock Exchange fell by more than half. Nevertheless, it was by no means clear at first, how severe the depression was going to be. Previous crises had originated in the United States--this was not the great novelty. What was unprecedented was the extent of European economic dependence on America which the crash of 1929 revealed.

This dependence varied greatly from country to country. Central Europe was involved first, as American financiers began to call in their short-term loans in Germany and Austria. Throughout 1930 these withdrawals of capital continued, until in May, 1931, the Austrian Creditanstalt suspended payments entirely. Thereafter, panic swept the Central European exchanges as bank after bank closed down and one industry after another began to reduce production and lay off workers.

Social Roles

The hypotheses suggested in the preceding chapter must be tested and developed by reference to case studies of human cultures. But which ones shall we choose? The comparative method yields data both from subcultures within a given cultural area and from distinct cultural wholes. As an example of the former we might compare Virginians with Kansans; as an example of the latter, Hopi Indians with the Ba Thonga of East Africa. Though both methods are feasible, the latter will serve our purpose better.

Data already in hand from interviews, questionnaires, clinical records, and historical and sociological descriptions, indicate gross differences in ego and in attitudes in different ethnic and religious groups within the rather uniform culture area of the United States; but these studies have two great limitations in relation to our present problem:

(1) They cannot at present accurately trace the diffusion of attitude from one group to another within the larger culture. At any given time the attitudes appearing in a subcultural group may be expressions of its own situation or expressions infiltrating from another subcultural area. Historical methods of a quantitative character would have to be devised to meet this difficulty.

(2) They cannot adequately take account of cultural lag. Ego formations or ego attitudes discovered in a given context of cultural events may reflect a situation which existed some time before but has ceased to exist; the persisting expressions of lag may be either stable anachronisms, or moribund vestiges which are doomed to disappear in time. Their true relation to the subcultural situation as it is at present is indeed obscure.

Data already in hand from interviews, questionnaires, clinical records, and historical and sociological descriptions, indicate gross differences in ego and in attitudes in different ethnic and religious groups within the rather uniform culture area of the United States; but these studies have two great limitations in relation to our present problem:

(1) They cannot at present accurately trace the diffusion of attitude from one group to another within the larger culture. At any given time the attitudes appearing in a subcultural group may be expressions of its own situation or expressions infiltrating from another subcultural area. Historical methods of a quantitative character would have to be devised to meet this difficulty.

(2) They cannot adequately take account of cultural lag. Ego formations or ego attitudes discovered in a given context of cultural events may reflect a situation which existed some time before but has ceased to exist; the persisting expressions of lag may be either stable anachronisms, or moribund vestiges which are doomed to disappear in time. Their true relation to the subcultural situation as it is at present is indeed obscure.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)